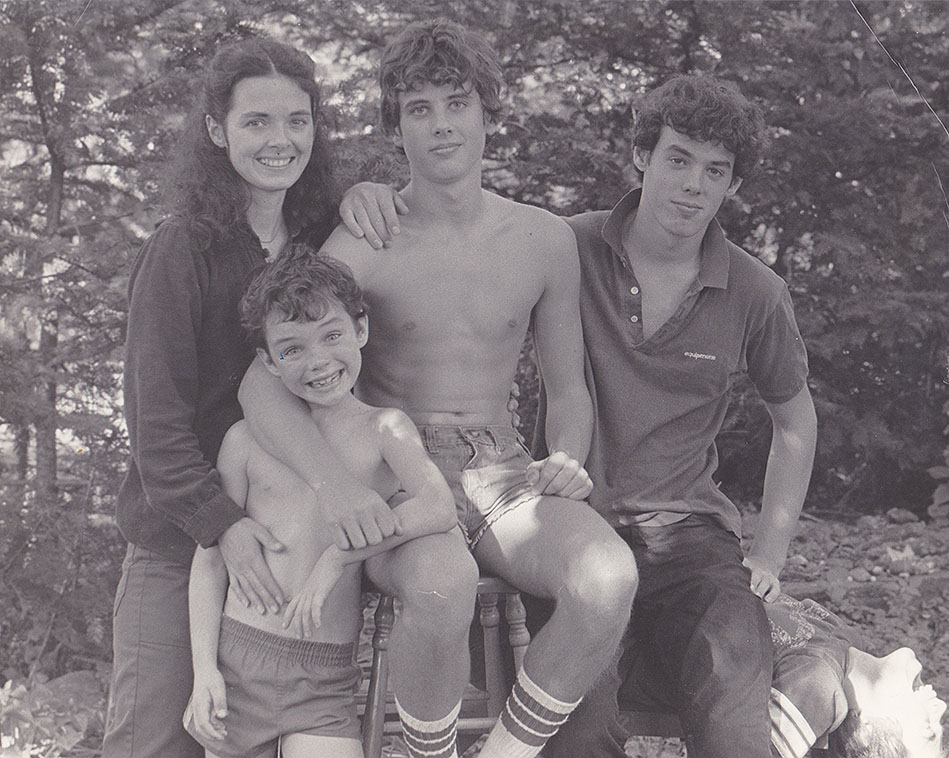

After my sister Maureen moved to San Francisco with her boyfriend Billy in 1965, my father took her a single lens reflex camera and a few rolls of film. Maureen had already had her first son Seamus, and Matt was on the way. Once she picked up that camera, it seemed she never put it down. The only thing she held more than the camera were her four beautiful boys. After she died at 37 of breast cancer, I stared at those photographs, hoping that I might reach her on the other side of the lens.

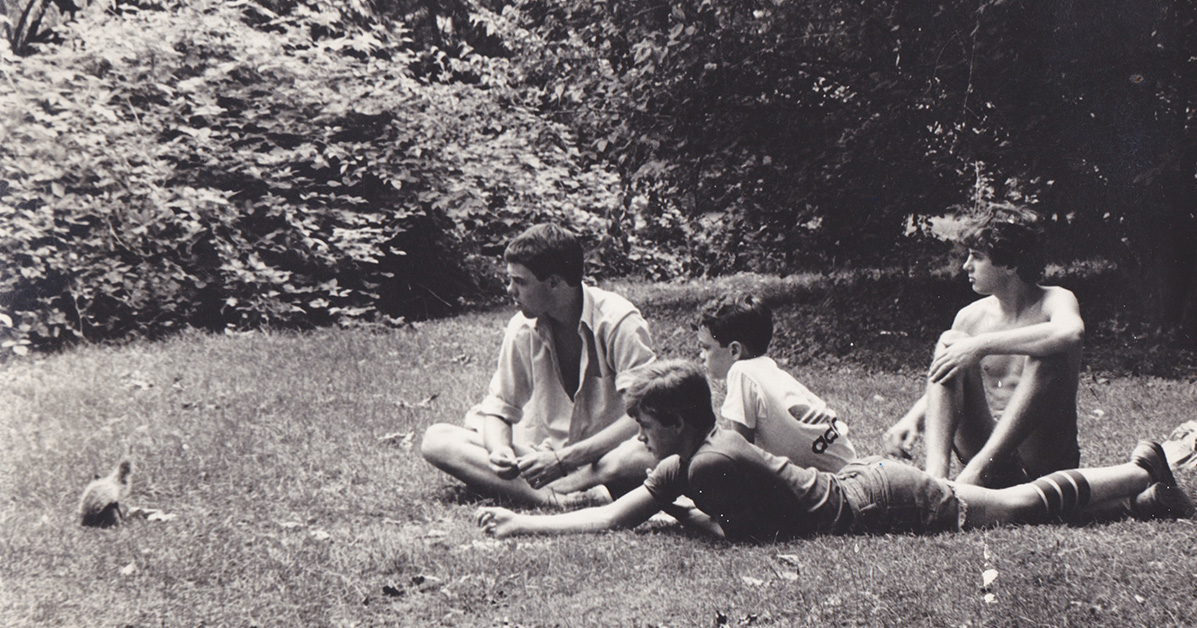

In September I spent five days with my sister’s sons: Seamus, Matt, Josh, and Liam. It is not hyperbole to say that they were five of the most precious days of my life. And now as I sit down to write a chapter of their lives — a chapter of my sister’s life — I know that no matter how long and carefully I consider these words, I will never do their experience justice. I will never honor my sister Maureen’s memory as it should be honored. And yet, here I am.

The occasion of this overdue gathering was the marriage of Seamus’ daughter Hope to Ganesh Sreeram. It was a beautiful meeting of families and cultures, culminating in a wedding reception that began with traditional Indian dance, followed by Irish step dancing, which included the bride and her sister Delia flying across the dance floor. Seamus read a Hindi translation of a traditional Irish poem that begins, “May the road rise to meet you.”

When I texted Seamus to let him know John and I would be there, he said there were events on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, as well as the wedding and reception on Saturday. So we flew to San Diego Tuesday and stayed in an Airbnb in his neighborhood. His brothers and their families had rented a house on the ocean in Mission Beach.

Wednesday’s events were a Mehndi for the women of the family and wedding party to get henna tattoos on their hands and, for the men, a bonfire on the beach. Seamus said I could go to either one, but he thought I’d have a good opportunity to visit with my nephews at the bonfire. So, I was the lone woman at the bonfire.

For weeks before this trip I lay awake at night wondering what feelings my attendance at this wedding would evoke. When Seamus was a freshman in college, Matt and Josh in high school, and Liam in middle school, their mother died. This virulent breast cancer followed an acrimonious and painful divorce, in which, although Maureen was given joint custody by the New Jersey court where they lived, she was often prevented from seeing her boys. After her death, it was made clear to the extended Reilly family that we were no longer a part of the boys’ lives.

The last time I had seen Josh and Liam was the occasion of their Garland grandfather’s service at Arlington Cemetery twenty two years ago. That weekend Seamus organized a gathering at the Four Provinces on Connecticut Avenue, not far from Jocelyn Street. There were probably twenty-five of us there, laughing and telling stories, catching up. We closed the bar, and I offered Matt and Josh a ride back to their hotel. When we got in the car, I said, “Should we drive by Jocelyn Street?” “Yes!” they both shouted. I drove up the avenue and made a left on Jocelyn Street.

When I stopped in front of the house, which had been sold when their grandmother died in 1995, Josh and Matt bounded up the front steps and across the porch, peering through the windows to see the rooms where they had spent so many long, summer days. I ran up behind them, saying, “Shhhhh. It’s the middle of the night. Let’s not get arrested.” They came down the front steps, but before I could get them into the car, they ran up the steep driveway and into the backyard. So many cookouts in that yard. So many games of tag and squirt gun battles. So many cousins and aunts and uncles, not to mention Geema and PopPop.

When John and I got to San Diego on Tuesday, we went to see Seamus and his family and meet Ganesh and his family. The next night we went to Mission Beach for the bonfire. The first person I saw when we arrived at the beach was Liam. He yelled, “Kate!” and threw his arms around me. I was touched that my appearance after so long was met with such warmth. And struck once again by how much he looks like his mother. The next hug was from my godson and nephew Matt, then his wife Joelle. I met Liam’s son Conor and saw Matt’s beautiful girls again. The sun was setting — beautiful, but a bit blinding, as well. I couldn’t quite see the big guy who came up and swallowed me in a bear hug. It was Josh, formerly known as the most beautiful baby. Now my trip was complete.

Not long after we arrived, Liam stood before me and asked, “If you don’t mind, would you tell me what you remember?” So, now I knew he didn’t just look like Maureen. That was just the kind of direct question she would ask. “What do you mean? What I remember of the divorce? Her death?” I asked. “Yes, all of it.” Now I was under the gun. How do I respect everyone involved but give him the truth of what I remember? He said he only remembered the bad things, like the hospital. But he also said that when he thought of his mother, he remembered her warmth. He remembered the warmth of his mother’s body next to his. There’s a saying about a child being carried for nine months just under his mother’s heart. For Maureen’s boys, this was followed by years of being carried on her hip, against her heart.

Their father was still an undergrad when he and Maureen went to San Francisco. After his bachelor’s degree, Billy went on to get a master’s and PhD. Maureen gave birth to the boys, fed them ramen noodles and homemade granola, made their clothes, kept them warm by knitting them sweaters and blankets, shopped at Goodwill for their shoes. All while her husband studied and worked at the lab.

Before Liam was born, Snugli started selling cloth baby carriers. Maureen decided she could make one just as well if not better. She made one for Liam with an outer shell of soft corduroy and a colorful print inside. There was a smaller inner compartment for newborns and an outer carrier for older, bigger babies. You could let out the pleats in both sections as the baby grew. When my sister Missy was pregnant with her son John, she made one for Missy and, years later, Maureen made one for my brother Brian’s wife Sara when she was pregnant with Annie.

When I was a teenager, I saved my babysitting money to buy tickets to San Francisco, spending a couple of summers with Maureen, Billy and the boys. In true 60s style, Maureen strung macrame on small, stripped tree branches and hung them from the windows. She hung a big Jefferson Airplane poster in the kitchen. They had a car but, mostly, we walked to the different neighborhood shops to buy fresh vegetables, meat from the butcher, and staples from a corner market.

One day we took the N Judah streetcar downtown and transferred to a cable car that went to Chinatown where we visited a store with a man behind the counter who only spoke Cantonese. He used an abacus to tally the cost of a wok and a couple of utensils. That night Maureen cooked a wonderful Chinese meal.

When Maureen found a meal in a restaurant she liked, she would grill the waiter for the ingredients. After they moved to New Jersey, she took us all out for a family feast at a restaurant in Manhattan’s Chinatown. It was the kind of place you find in New York that’s hidden between streets, inside an arcade. There was no menu and the meals were family style. Each time the waiter brought another item, Maureen asked, “What is this? What’s in it?” Each time the waiter responded, “Special appetizer……Special noodles….Special chicken….Special pork.” He was giving her no information, but Maureen was undeterred. She kept asking, “Yes, but what else is in it?” The meal was delicious.

Caring for her family was Maureen’s joy. All of the knitting, sewing, cooking, and even the cleaning made a better life for her sons. As old-fashioned as it sounds, this was her world, and it made her life complete. Typically, she had a baby on her hip with the other boys in tow, headed to the playground or a museum or a soccer game.

But if Maureen came across anyone who might hurt someone she loved, she was fierce. On a hot, summer’s night in the apartment on Grattan Street, Maureen left the windows open. Billy wasn’t at home. At around midnight, Maureen awoke to find a man standing in the doorway. Apparently, he had come in through a window at the back of the apartment. She sat up in bed and screamed, “What are you doing here?” He got frightened and ran down the hall and out the back door.

When my brother Kevin was in a rehab hospital in New York after his motorcycle accident, Maureen and my mother made the daily trek into the city to see him. It was too hard to deal with parking, so they took a bus to the Port Authority and switched to a crosstown bus to the East River. One night they were headed back to Maureen’s place, waiting at the Port Authority for the bus to the ‘burbs. A man sat on the bench next to Maureen and exposed himself. She stood up and screamed at the top of her lungs, “Get away from me, you fucking pervert!” He scurried away. Maureen looked at Mom, who sat with her mouth agape, stunned by the man and by her sweet and beautiful daughter’s reaction. “He was relying on my embarrassment to keep me quiet,” Maureen calmly explained.

The divorce was Maureen’s decision. The move to New Jersey was difficult for her. It seemed that all the doing without through undergrad and grad school had left Maureen a second class citizen in her marriage. She felt she would never be an equal partner. But in leaving her husband, she unleashed an anger in him she had not anticipated.

Missy remembers being with Maureen one day when she picked up the boys from their father and stepmother’s house. They stood on the front porch and screamed at Maureen to “stay off our property!” Missy, who was brought up in the “nobody messes with my sister” Reilly clan, started to respond in kind. Maureen turned to Missy, put a hand on her arm, and said quietly, “Not in front of the boys.” She would take the humiliation if it spared her sons.

Since she had spent the first decade and a half of her adulthood raising her boys and making a home for them, Maureen had no source of income after the divorce. She did take beautiful photographs, so she got a job waitressing to supplement her work as a professional photographer. Mostly, she took portraits and shot weddings. Initially, she rented a one-bedroom apartment not far from the boys. In order to have a place for the boys to stay, she built two sets of bunkbeds in the living room.

While Maureen was dying, I called her ex-husband, who had been a brother to me for many years, to ask if the older boys might be able to spend some time with her on the weekends. “She is not their mother,” he said. I found his words so dissonant that I could barely speak. I had the strong sense my words would never reach him in any event.

At the rehearsal dinner in San Diego, I went over to speak with Jane, my nephews’ stepmother. I told her that if Maureen could pop down into the this happy event, she would thank Jane for loving her boys. Jane, with tears in her eyes, told me that as Maureen lay dying, she said, “Jane, they are yours now. Take care of my boys.”

And what beautiful men they have become. All of them, kind husbands and nurturing fathers. On the beach that night, Liam also asked, “What would she think of all this?” “It would be her bliss,” I replied. To a man, her sons have become genuinely good people, but that is no surprise. The imprint of her loving spirit is woven through them.

Over the course of five days in September, I saw her goodness in each of them and their children. In the proud way Josh spoke about his daughter who excels in cheer (I was wondering if she would cartwheel into the wedding reception, but her mom pleaded with me not to suggest it.). In the sweet way Matt wanted to share his daughters with me and me with them — I threw off my shoes at the cocktail hour to play cornhole with them. I saw it as I watched Liam gently guide his cheerful, curious son Conor, who hadn’t known that his great, great grandmother Annie O’Connor Reilly shared his name.

Over the course of all these events focused on love, the most tender moment came when Seamus walked Hope down the aisle. Proud and apprehensive. Clearly not wanting to let her go, yet excited for the life before her. I know it was that early steadfast love from his mother that gave him the strength to trust Hope enough to let her go.

When someone you love dies, the memories take on a dream-like quality. In time, they become slivers of memory: a scar on her cheek, a pair of worn bell bottoms, a half-smile in dim light, the gentle sound of her voice. Sometimes it’s hard to distinguish the memories from the dreams.

All the events for Hope and Ganesh’s wedding were in the evening. Each morning John and I walked through Seamus’ neighborhood to a little French cafe. We sat outside eating our crepes and scrambled eggs. John with his coffee and me with my tea. The memories and dreams merged, and the tears slid down my cheeks in the warm California sunshine.

Thought I was going to cry! So we’ll written Kate, thank you for sharing, love you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh Kate…. you do have a gift. So many great stories in one story. Thanks so much for sharing this one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So beautifully written! What a precious way to honor your sister and her boys.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful, Kate

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully shared Kate… thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person