My father was eight years old in the 1918 influenza pandemic. His father died in the second wave that hit the U.S. in the autumn of that year. On Armistice Day, Annie Reilly and her five children were headed to Peter Reilly’s funeral. Crowds filled the streets of Pittsburgh to celebrate the end of the First World War. Dad asked his mother if all those people were in the street for his father’s funeral.

When the depression hit in 1929, the Reilly family headed to Washington, D.C. Dad was the last to leave the house in Pittsburgh, and his mother told him to bring the linoleum from the kitchen floor. So, he rolled it up and carried it onto the train. In Washington, he got on the trolley car that ran up Wisconsin Avenue and promptly fell asleep. When he woke up in Friendship Heights, he realized he didn’t have enough money to get on the southbound trolley. He walked from the Maryland line all the way down to Glover Park with his suitcase and that roll of linoleum.

After exhausting their employment opportunities, Dad and his brother James got scholarships to law school. Their mother told them to get a trade like their brother Martin who was a plumber’s apprentice. Marty was actually earning a living. During law school, Dad worked at the Peoples Drug Store on Dupont Circle.

In his last year of law school, Dad got an internship at the FBI. I still have the letter he received at the end of his stint there, commending him for his service and wishing him well in his career. It was signed by J. Edgar Hoover. Dad would smile proudly and say that he’d been fired by J. Edgar Hoover, the man who persecuted Martin Luther King, Jr. and wore dresses on the weekends. I don’t think Dad minded the dresses so much; it was more the hypocrisy.

My parents met at the U.S. Capitol. In the mid-thirties, Dad worked as a staff attorney for the House Committee on Civil Liberties, and my mother was in the secretarial pool. There were no audio recorders for committees, never mind video. Young women, like my mom, would sit in the hearings and write everything down by shorthand. Then, they’d go back to their offices in quonset huts on the Mall to type up the proceedings. (As I look back, I am confused as to why my mother, who had a degree from the University of Nebraska, was working as a recording device, but it was the Depression and she was just a girl, I guess).

One of the companies the committee was investigating was the Ford Motor Company. The United Auto Workers were trying to organize the workers at a plant in Dearborn, Michigan. There were reports of union-busting at Ford plants, and Dad went to see what was up.

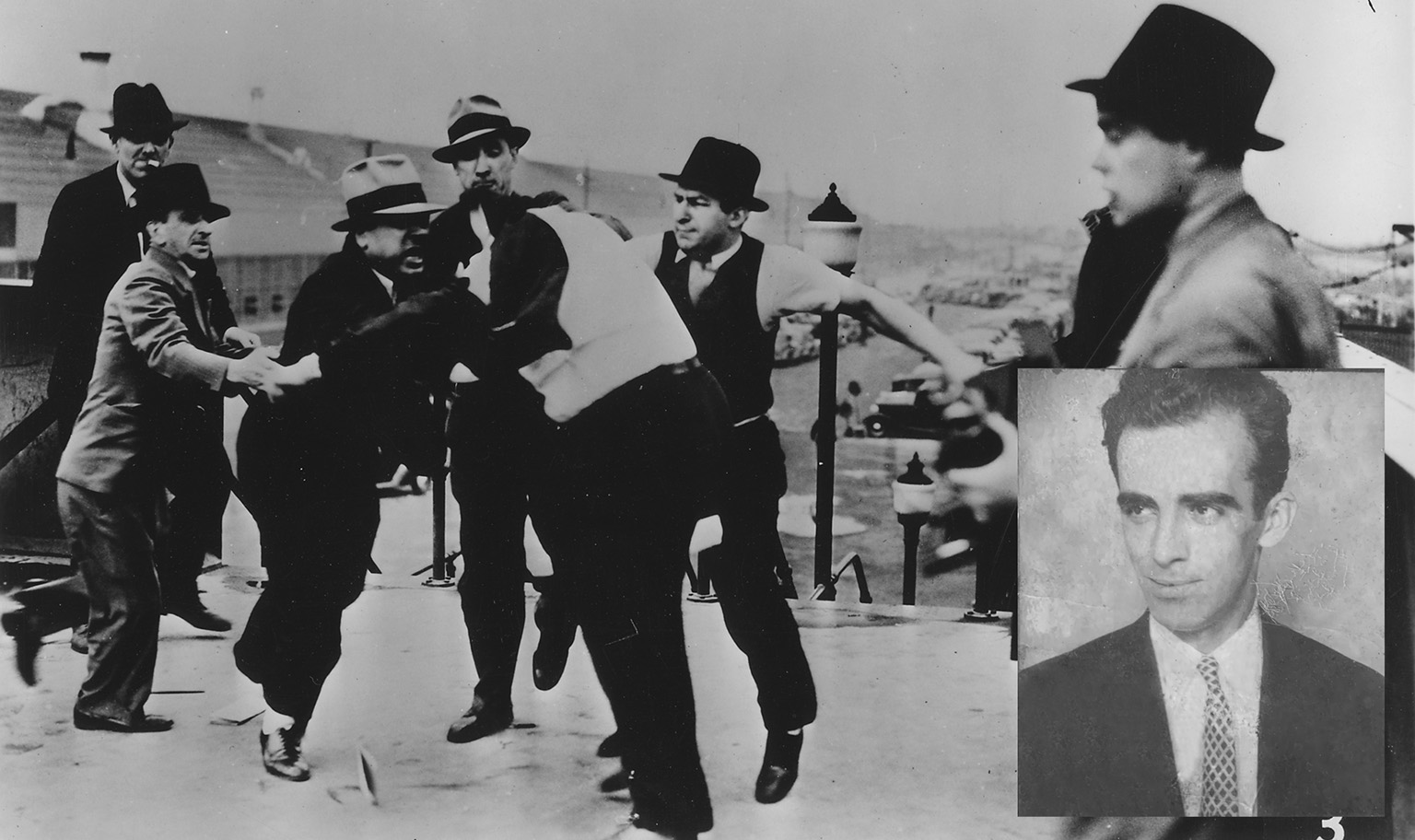

The incident Dad witnessed is known in labor union history as the Battle of the Overpass. The UAW organizers came to hand out pamphlets and talk to workers. Ford “security” officers (Dad called them “thugs”) headed toward them on an overpass that spanned two assembly line buildings at the plant. Dad arrived at the moment the two groups converged, as did a photographer from the Detroit News, as luck would have it.

The union organizers were greatly outnumbered and got beaten badly; a man was thrown down the staircase from the overpass. Others were body-slammed into the cement. But, as in the videos of January 6, the world would soon know exactly what happened. Besides newspaper accounts of the confrontation, Life magazine ran a story the following week. Those accounts turned the tide of public opinion in favor of labor unions. Ford made Dad’s investigation of union-busting pretty straightforward.

When I came along, my father was at the height of his career, working as Vice President of Transocean Airlines. Transocean began international flights just after World War II. In addition to passenger and cargo flights, they worked with governments to get their own airlines going — training crews and providing planes.

Dad was part of the team that negotiated with the Saudi royal family for the contract to start up Saudi Arabian Airlines and with the Japanese government for Japan Airlines. The latter was a delicate proposition since it was shortly after some of those same executives had flown missions in the Pacific, fighting a war with Japan. But in both cases, they won the contracts. Transocean was also a major participant in the Berlin airlift, bringing food and supplies to Berliners when the Soviet Union set up a blockade to try to get western countries out of West Berlin.

But to me he was not the brilliant legal mind or the master negotiator; he was just my father, a kind and gentle man. That kindness was evident when his mother-in-law (known to us as Gram), who had been divorced by her husband of thirty years, was left with next to nothing. My grandfather’s attorney, who was also Gram’s attorney — in an act of bizarre legal malfeasance — gave her a check for $1,500 to live on for the rest of her life.

For a year or so, she worked in a chocolate factory. I imagine her standing in front of an assembly line, looking like Lucille Ball, and stuffing her cheeks with chocolates but, in fact, she worked in the office.

When it became clear that this endeavor was not financially sustainable, my dad wrote her a letter — not saying that he would come to her rescue. He told her it would be a tremendous gift to him and to my mother if Gram would come east and help take care of his growing family. It was a loving and thoughtful letter, affording her all the dignity that the divorce had not.

There’s an old adage that the greatest gift a man can give his children is to love their mother. And that my father did. He would come through the door after a day of work, and Mom would walk out of the kitchen to meet him. He would take her into the empty dining room, away from prying eyes, and give her an “in the movies” kiss, as my sister Missy said, which would send us all into giggles.

Clearly, they adored each other. We teased Dad for decades after he reprimanded Dennis for speaking disrespectfully to Mom by saying, “You are speaking to the woman I love!” And when one of us was being particularly difficult, Dad would turn to Mom and say, “I don’t know why you wanted to have all these damn kids, anyway!”

My father was 45 when I was born. He didn’t teach me to ride a bike or throw a baseball. But he did teach me to love words. He wrote beautiful letters to my mother and exquisite legal briefs. After I moved out of the house and couldn’t find a word in the dictionary, I would call him. He always knew the definition. And he wasn’t the kind of guy to make up something rather than admitting he didn’t know. Once I called him from New York and said, Dad what’s the Phoebe Snow? I had seen the name on the side of an abandoned train car in Brooklyn, and I only knew it as the name of a singer. He said, It’s the Erie-Lakawanna train line in Delaware.

Sometime after he died, I was flipping through the Websters dictionary on the shelf of the third floor landing at Jocelyn Street. I found a crossword puzzle that Dad had nearly finished. All but one letter. I reached for a pen and added the final letter. He knew the letter; I’m sure he left it there for me.

When I was twenty-one, my father was diagnosed with advanced emphysema. Between growing up surrounded by steel mills and smoking Phillip Morris cigarettes for most of his life, his lungs didn’t stand a chance.

One afternoon in early February, he and I watched To Kill a Mockingbird together. Toward the end of the movie, Boo Radley is found hiding behind the door in Scout’s bedroom. Dad pulled a handkerchief out of his pocket, and I waited for him to cough into it, as I had seen him do a thousand times. Instead, he took off his glasses and wiped his eyes. It may be the only time I saw him cry. Twelve hours later he was gone.

He was my Wikipedia, my Websters, and my Atticus Finch. And I was his Scout.

What a beautiful picture of Uncle Joe! I wish I’d known him better. I hope one day you and I can spend time together sharing our history and Reilly heritage.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would absolutely love that, Francesca. We’ll get together post-Covid and share some stories.

LikeLike

This is unspeakably lovely. That’s seems lie a strange way to put it. This is such a tribute to a honorable, loving, smart, kind man. What an interesting life he lived. How lucky you were to have such a father.

—————————— Anne Stonehill 917 612-0597

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re sweet, Annie. I was lucky, indeed.

LikeLike

Kate, brilliant as usual! You had me wiping a tear away. Thanks! Big Hug!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hugs to you, too, Chris.

LikeLike

Kate, you are the Lewis Gates, Jr. of the Reilly family!! I love this story and it brought tears to my eyes. I remember one Christmas when Rita and Nina were one and two, we had practically no money for Christmas for these two adorable girls, and your dad pulled Joe aside and said “Here take this money and buy those two girls something for Christmas.” I have to say between my parents and your parents Joe and I received help and love when we needed it the most

From: Life of Reillys Reply-To: Life of Reillys Date: Sunday, February 21, 2021 at 4:39 PM To: lane Subject: [New post] The Man Who Loved My Mother

Kate Reilly Brinkley posted: ” My father was eight years old in the 1918 influenza pandemic. His father died in the second wave that hit the U.S. in the autumn of that year. On Armistice Day, Annie Reilly and her five children were headed to Peter Reilly’s funeral. The crowds filled t”

LikeLike

What a sweet story, Lane — and one that I’d never heard. You know better than anyone that I couldn’t do this without the next Joe Reilly. He’s been such a great source!

LikeLike

Kate,

So poignant and well written. It touched my heart. Maybe you write something that nice about my dad?

There’s a challenge for ya. You were a lucky gal. 💕

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Holly. I was a lucky gal.

LikeLike

Loved this latest post, Kate. What a gift that you remember and record!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Lyn. I’m lucky to have siblings who provide details!

LikeLike

You Dad sounds like he was a great guy that set an example for his children by how he lived his life and treated those that he loved. A life well lived.

LikeLike

He did set a great example for us. My sisters and I have talked about how hard it was to replicate their love story. My guess is that we only saw what appeared to be a perfect love, without the dirty sox and missed dinners. But their story was aspirational for all of us.

LikeLike

Kate,

Thank you for the absolute joy i had in reading these posts. This post in particular was one of the sweetest thing I’ve ever read. My mother used to tell the story of your dad preparing Grandma Reilly a tray of tea and toast with a flower on the tray when she had one of her migraines. She always described him as the gentlest man…quiet like her, but ferociously protective. To Kill a Mockingbird was the first big girl book I ever read. My sister MaryAnn gave it to me when I was 10 and feeling sorry for myself – we had moved from Ruskin Ave and I was miserable. She told me I would never be able to finish it, which of course, I had to prove her wrong. To this day, it’s still one of my favorite books. Needless to say, I was in tears reading your ending. How special you are letting us all in on those beautiful memories.

Thank you for sharing!

Love to all the Reilly’s

Patty McAuliffe

LikeLiked by 1 person

Patty, thanks for your kind words. I loved reading To Kill a Mockingbird, too. When I had a captive audience in my daughter Maeve, I read it aloud to her — maybe to give her an idea of the kind of guy her grandfather was. And I never knew that story about our grandmother until I read our reunion notebook. On top of all the other things she had to deal with, she had migraines. Such a hard life! I hope you’re doing okay with the craziness of the past year. We won’t make it to the cape this year unfortunately, but I’m still planning on coming to see you when we do. Take care.

LikeLike